Control with Contingencies at Armani

A strategic succession plan was the fashion icon's final design

New this season on “The Owner’s Box,” our mini episodes are on video. Watch here, listen to audio only, or read below. Let us know which format is your favorite!

One week before the passing of Giorgi Armani, the Financial Times ran an interview with the iconic fashion designer. If you are interested in ownership, entrepreneurship, or the fashion industry more broadly, it’s well worth your time.

Specific to the company’s future, Alexander Fury’s opening lines are worth noting:

“The hallmark of Giorgio Armani is control. At 91, he remains not only creative director but also CEO and sole shareholder of the company he founded 50 years ago.”

And this company, no mere mom-and-pop operation, had revenues of $ 2.7 billion USD. That is a significant amount of control held by a 91-year-old, a risk, obviously, given his eventual passing this summer.

What does it mean to have strategic control versus being an overly controlling owner?

Strategic Succession Planning at Armani

With such a concentration of creative control in one person, strategic succession planning is vital. It’s worth exploring, then, how Armani was setting up his company to last far beyond him. He hints at this in the FT, saying,

“My plans for succession consist of a gradual transition of the responsibilities that I have always handled to those closest to me…such as Leo dell’Orco, the members of my family, and the entire working team.”

But it was only after his passing that the structure was revealed. Here’s how it plays out.

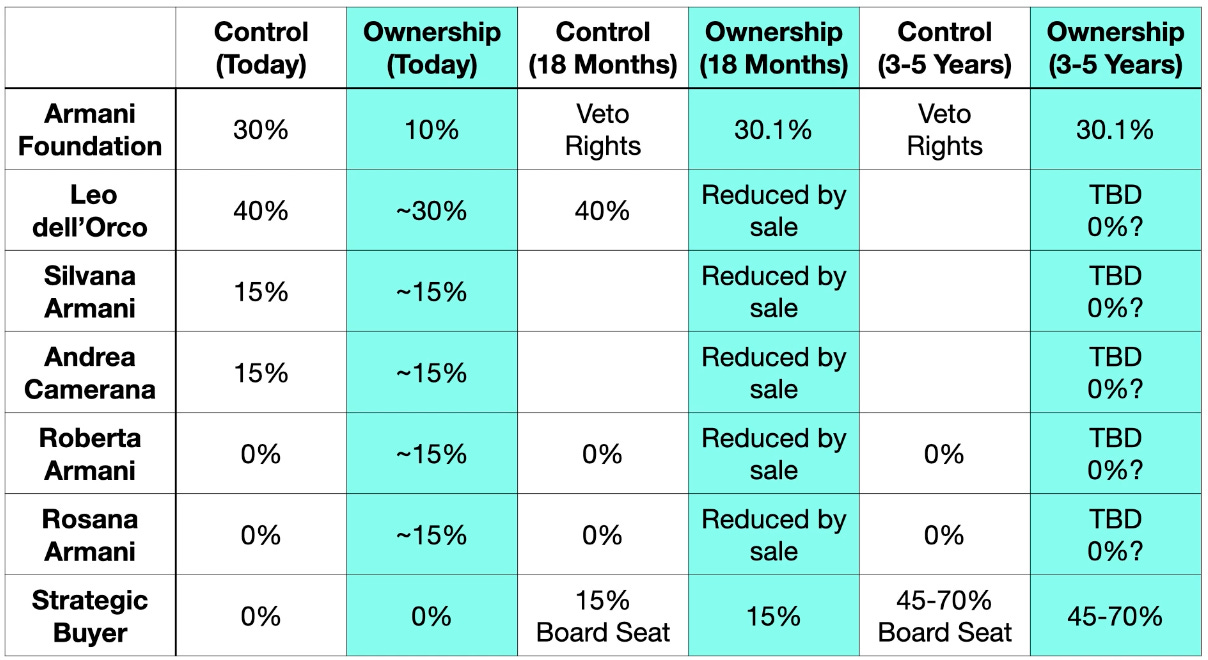

Armani’s will distributes the capital and voting rights in different proportion. First, let’s focus on the voting rights, the key factor for determining the decision-makers in shaping the company’s direction and legacy.

In the company’s new form, the Giorgio Armani Foundation holds just over 30% of the voting control—and always will. Dell’Orco, one of Armani’s long-time designers and leaders, himself in his 70s, is set to hold 40% of the company’s voting shares. Together, the creative designer and the foundation hold 70% of control over all major decisions. The remaining 30% is divided between two members of his family, Silvana—his niece—and Andrea—a nephew by marriage. Both have significant experience in and understanding of the industry and the company in particular.

The capital is spread more diffusely, counting in two additional family members: Armani’s younger sister, Roberta, and his niece, Rosanna. Each have a 15% stake, as do Silvana and Andrea, with 30% going to partner dell’Orco and the remaining 10% held by the Foundation.

But here is where it gets interesting. The shareholders must sell 15% of those shares within the next 18 months to a value-aligned buyer, a group such as LVMH, L’Oréal, or EssilorLuxottica. If one of these top three doesn’t have interest or is not the right fit, for whatever reason, the controlling owners hold the rights to determine who would fit the bill.

After the sale, dell’Orco will keep his 40% voting rights, despite a smaller holding, and the foundation will retain veto power on major decisions including all M&A activity. Think of this like a dating period, during which those closest to Armani’s vision can still decide to walk away. Then, within 3-5 years another 30-55% must be sold either to the same buyer or, if that does not occur, via a public offering.

When you play this out, this means that this new buyer would own between 45% and just under 70% of the company, with the Foundation retaining the minimum 30% ownership as stipulated in the will. Within 3-5 years—the average shelf life of a bottle of Giorgio’s aptly named “My Way” perfume—Armani could be a Foundation + Fashion Company held entity...just not by their original founder.

So, what makes this interesting?

The Imaginative Possibility of Contingent Control?

Control beyond the grave like this can wreak havoc on companies. And I think Armani was aware of the dysfunctional version of control. The article goes on:

“My greatest weakness is that I am in control of everything.”

Since his passing, the stakes are even higher: the brand is at risk if Armani the company is too tightly associated with Armani the man. How do people see the company without that leader at the forefront, both in the details of the design and the strategy of ownership?

Armani’s vision seems to be that with the right buyer, his values and the value proposition of his brand, will carry forward—if those closest to him can identify that buyer and close the deal. His entire succession plan structure is a kind of if / then approach. If this company is a good fit, then let’s sell the rest of it to them. If members of my family want to get out ownership, then they will have right buyers to do so.

And notice how all the initial if is still controlled by the designer and foundation tasked with holding to a set of critical values for the firm.

Is this the perfect solution? I’m not sure. I keep thinking back to my interview with Stuart Weitzman from Season 1.1

“Corporate mindset should not buy entrepreneurial businesses. I’m convinced of that. I’ve heard too many bad stories about it, including mine. They shouldn’t. It’s a different approach. Listen, I had five people in my design team and two analysts. They have 12 analysts and two designers. What’s important to them? And what was important to me? And six years later, they do half of what we did.

It’s a different mindset. It works for Häagen Dazs because it’s one product, you know, and, and it works, I guess, for cups or steel rods. But something that changes every three, four months—not 100%, but say 40% of the product mix has to change to stay active and alive. They can’t, they’re too slow. The corporate mindset needs time. It really does.

My turnaround was six weeks from a hot idea to offering it to my customers. Theirs is seven months. They’re designing 2025 winter collection when 2024 hasn’t come yet to tell us what maybe is new that’s hot.”

I heard in Stuart, also the consummate controlling creator, a sense of loss from selling his company—a sense that the organization is different with new owners than it would have been had he been able to hold on.

So will this potential challenge be addressed in the Armani model? Perhaps! Think of it as a two-step approach.

First, the Foundation plus dell’Orco—a set of people with multiple perspectives and unique insights—might be better positioned than a single individual, no matter how brilliant, to discern buyer fit on the front end. If so, then they might be able to increase the likelihood of a good match.

Second, I really like how this approach allows you see the proof in the pudding. Let’s say they pick a buyer and it goes poorly. At this point, you still have 70% of the voting shares making the call on whether this dating period should proceed to marriage.

Control with contingencies, in other words. Maybe this is the last brilliant insight from the creator: that the most innovative solutions will ultimately come out of things you could not have imagined from the beginning.

Photo credit: https://tech.caltech.edu/2024/12/03/interview-with-stuart-weitzman/