Stewarding Potential and Exploring Vocation with Katie Ford

Exploring vocation within a family business--a conversation with Katie Ford of Ford Models.

In the most recent episode of “The Owner’s Box,” I sat down with Katie Ford, former CEO of the iconic modeling firm Ford Models. What I loved about the conversation was the chance to connect with Katie and hear what it means to her to steward a certain legacy, all while being open to what is required to explore something new.

We all innovate from a particular starting point. I am the son of Jane and David, a social worker and a pastor. I grew up in the western suburbs of Chicago. Those who know them or that place might have certain impressions of who I might be and what I might pursue. But from those constraints, we also have opportunities — if we take them — to extend beyond this start.

For some, that pressure of alignment is more acute. I think it is fair to say that Katie had a bigger burden than most. Katie’s mom, after all, is one Eileen Ford, the co-founder of the modeling agency of her namesake. In their 2014 obituary, the New York Times had this to say about the co-founder of Ford Modeling, Eileen Ford. She is:

“The grande dame of the modeling industry (someone) who influenced standards of beauty for more than four decades while heading one of the most recognizable brands in the trade of gorgeous faces.”

From its start all the way through Katie’s tenure, Ford was a company that launched and stewarded the careers of icons. Christie Brinkley, Naomi Campbell, and Elle Macpherson—Ford made them household names. Jane Fonda, Brooke Shields, and Candice Bergen—Ford was a big part of what moved them from the catwalk to the silver screen.

In this episode, Katie and I focus on what it means to steward that iconic history, all while being open to what might come next—both within and outside the firm. Given that we all inherit and evolve some story, I think there are lessons for each of us here.

Finding Career Alignment

As most of you know, my day job is as a professor. This means that much of my time is spent helping people find what they care about in the classroom and in one-on-one meetings. A good bit of my relatively new role in the Provost’s office centers on bringing that kind of exploration of purpose and opportunities for impact to scale.

But as much as I believe in the importance of this, I also think it can be debilitating. After all, how many of us really feel like we have found a deep sense of calling in our careers? My own undergraduate institution liked to counsel us to identify some intersection between the world’s greatest need and our greatest passion. But then I graduated and started making photocopies for my grad school professors, and others started knocking on doors to sell insurance. The disconnect was real.

You can hear a bit of this same challenge in finding fit in Katie’s reflections on her early work in consulting right out of grad school:

When I took the consulting job, at first, I thought it sounded very, very interesting. But then I got to experience the actual job. First of all, everybody was brilliant. I, on the other hand, wasn't the best consultant.

One time, I remember the head of the company asking the question, "Well, how should we tell companies how to run in this environment of 18% interest rates?" This was around 1980 and I had absolutely no idea. I didn't even know the right questions to ask. But there were others in the firm who had economic degrees. They knew the answer. They could be credible in their response.

In another engagement, I had to visit beer distributors across the United States. They looked at me like, "What is this person even doing here?" But because we were reporting to the company chairman, they had to talk to me.

So, after about a year and a half and a few engagements where I worked with clients, I realized this was really not for me. It wasn't satisfying. I wanted to be more hands-on, connected to an art form, and travel to interesting places. At that point, I realized I had just described my parents' business. That's why I decided to join the firm.`

Can any of us really understand fit before we step in to t something? Can an 18-year-old who said they always wanted to be a doctor really be trusted in their own self-assessment?

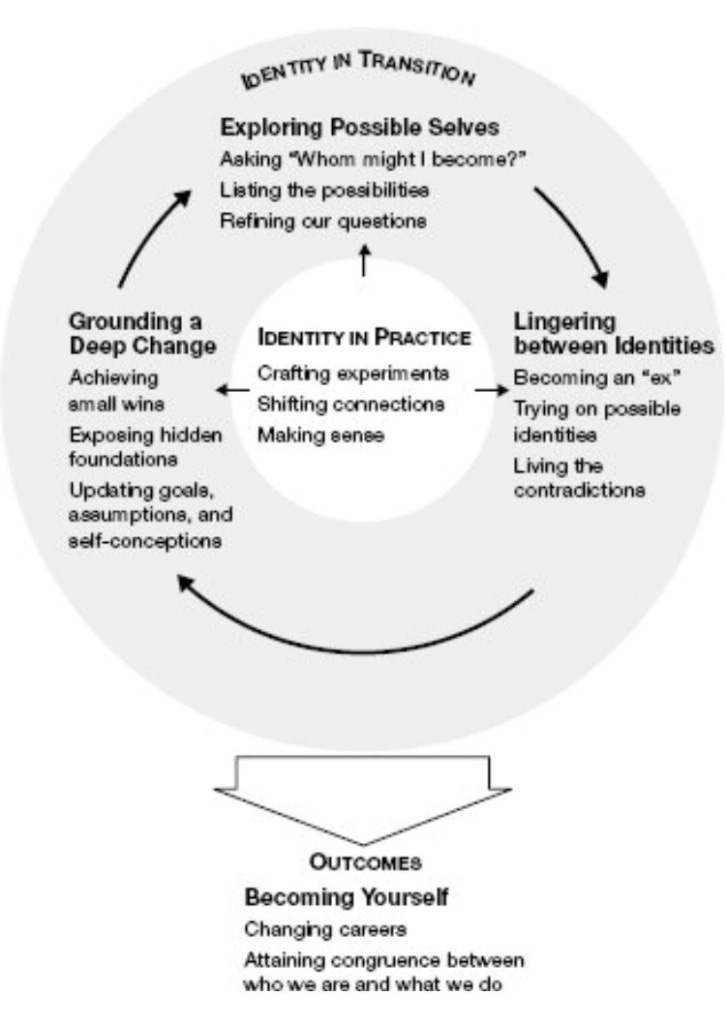

On this point, in particular, I have found Herminia Ibarra thoughtful. Her 2003 book, Working Identity: Unconventional Strategies for Reinventing Your Career, introduces the concept of “provisional selves” to a wider audience. Ibarra argues that in times of transition, it is counterproductive to hold onto what you see as your “authentic self;” rather, one can benefit from trying on different kinds of “selves” to see if they fit and eventually craft something that aligns. Put another way, this is not to say that one can’t find purpose and impact before action, but rather that it is more often found on the path of experimentation.

Evolving an Organization: Are you the best owner?

If it is difficult to experiment with an individual self, it can be even harder when doing so with an institution. When you take over an organization (or lead a group or team) and want to do something new, you inevitably push against what has been done in the past.

A second theme of our conversation was Katie and her family’s exploration of and eventual sale of Ford Models in 2007. These kinds of choices can be especially fraught, knowing you are both carrying on the legacy of your parents but also trying to be attentive to what is in the best interest of the family and the company.

As many of you know, I generally like it when owners find a way to keep an asset private. This decision to hold can be an opportunity to steward this organization into something new.

At the same time, I also know that there are times for transition. When we started teaching together, my friend and co-instructor Spencer Burke sent me a McKinsey article titled “Are you still the best owner of your asset?” At the end of the day, this is the key question that Katie and her family wrestled to answer. It’s worth a listen!

Bigger and Faster than a Non-Profit

This all brings me back to Katie’s career evolution. I just started reading Anne-Laure Le Cunff's new book called Tiny Experiments: How to live freely in a goal-obsessed world.

The framing of Anne-Laure that I keep returning to is her mapping of people on two dimensions — ambition and curiosity. Taken together, it looks like the following:

One of Le Cunff’s points is that ambitious people often migrate to the lower right quadrant—one characterized by low creativity. This involves actively avoiding experimenting with new paths. I see this amongst many of the students at WashU: They are very clearly high in ambition but sometimes too narrow in their vision of what to explore.

But this is not limited to students. For those of us later in our careers, the push to limit curiosity is even stronger. In pushing in one direction for an extended period of time, we generate so much momentum to keep moving in this same linear path. Think of all the time and energy YOU have put into your current path! Now is not the time to explore. Focus! Seek efficiency! Keep digging in further!

But sometimes, we need to explore! At certain points, we need to open our eyes and see what is out there, a kind of attention that doesn’t necessarily involve losing ambition.

For Katie, after the sale of Ford, this exploration meant following an invitation to pontificate on the problem of human trafficking. It eventually meant discerning how this was best done through a mix of non-profit and for-profit structures. Here she is on that exploration:

When I left Ford, I was actually going to do something else. But the UN had asked me to come speak at a conference about human trafficking. The term human trafficking was not widely known at that point, and when I looked it up on the internet, there wasn't very much available. So, I told them I'd never heard that term, and wouldn't you like someone who knows what they're talking about to come speak? But they said no — they wanted women leaders in business and government with relevant experience to explore this together.

So, I went to the conference, and I immediately knew why I was there. How people get trafficked is the same way we scouted for models. We went, and we told them what the job was, what the situation was like, and what amount of money they might make. And we tried to make that actually happen.

In trafficking, a person is told whatever the job is, whatever they want, and yes, that they can have it and they’re going to make a lot of money. But when they get there, they've been duped and forced into a different job where they don't earn money. It is something I could really understand. I could imagine that happening to our models.

And so I thought, I have to do something about this, and I have to do this full time. In our non-profit work, we partner with individuals and organizations around the world. I also started a business in the Middle East. In this work, I basically had the idea of applying my parents' values to a domestic worker business. Could we protect them and help them make money? And so far, we've done that; we've had over 10,000 women work for us there. And I did it because I was trying to do something bigger and faster than I could do with my not-for-profit.

Obviously, this episode is about Katie, Ford Models, and the work in the owner’s box to connect the two. But more broadly, it is an episode that explores what it means to evolve over the course of one’s career. How do you find paths for innovation, experimentation, and space to trial provisional selves? How do you build the muscle of curiosity as the pull toward ambition or perceived sense of momentum too often squeezes that out?

I hope you enjoy it. If you haven’t, please sign up for the podcast wherever you listen. In our next full episode, I will discuss the lessons learned by folding employee ownership into private equity investment with Anna-Lisa Miller, Executive Director of Ownership Works. I hope you will join us!

Show Notes

If you are interested in learning more beyond the episode and newsletter, please find below a few resources we used in the generation of this episode:

For more on this work Katie is doing today, take a look at the following two articles:

For more on Katie’s mom Eileen, and the work to build the iconic modeling company into what it became:

“Eileen Ford, Grande Dame of the Modeling Industry, Dies at 92” New York Times

“Four Supermodels that Changed the Fashion World.” New York Post

For two books that do a good job of bringing to light models for thinking about experiments and career evolution: