Ownership & Invention: From Ring to Rural Missouri

Lessons on invention and economic development from Jamie Siminoff

It’s 2013, and a young Los Angeles entrepreneur steps onto the Shark Tank stage. His company is DoorBot — a scrappy startup with a simple but strangely compelling idea: a video doorbell that lets homeowners see who’s at their front door from anywhere in the world. He’s asking for $700,000 for 10% of the company.

“Caller ID for your front door,” he pitches.

Mark Cuban smirks. “Because all criminals ring the doorbell first?” he quips, half-joking, half-dismissive.

The entrepreneur doesn’t flinch. “Actually, they do,” he says. “To check if anyone’s home.”

Over the next few minutes, the sharks drop out one by one. Too niche. Too risky. Even with a lead in the market, too easy for Amazon or Google to catch. The lone holdout is Kevin O’Leary, a.k.a. Mr. Wonderful. He’s got an offer—but it comes with strings.

“$700,000,” he says, “for a 10% royalty on sales until the investment is paid back. Then, the royalty drops to 7%… forever. And I still want 5% equity.”

The entrepreneur does the math. And then, astonishingly, he walks away (full video here).

So here’s the real question: Would you have made the same call?

Well… it turns out that this entrepreneur—one Jamie Siminoff—was willing to sit down with us as a guest on the most recent episode of The Owner’s Box.

For those who don’t know the story, DoorBot eventually became Ring—the billion-dollar home security giant now sitting under the Amazon umbrella. Today, it’s one of the largest home security companies in the world.

In this episode and our corresponding newsletter, we want to take you inside the mind of Jamie, pulling lessons from his position inside the Owner’s Box, and how it has shaped his work in both business and community development in small-town Missouri.

The Discernment of a Capital Partner

One of the things I find especially interesting about business schools is the almost mythological status assigned to raising capital. It is proof that someone, somewhere, believed in your idea enough to give it a check. But put another way, raising money just means you gave away part of your company.

Jamie Siminoff sees it differently.

In our conversation, we dug into the challenge of scaling a fast-growing company and the pressure that comes with it. In many ways, Ring had to raise money to scale quickly, but this put all the more pressure on finding the right partner.

Here is Jamie on one tactic he used to discern investor fit:

At Ring, we got super lucky with our investors early on. We had just had an awesome group of mission backing investors. A lot of it was luck, honestly, because I probably would have taken money from the devil at certain times because I needed money.

As we got further along in the fundraising and became a hot commodity — something like our C or D round, I made the decision to make three different PowerPoint presentations. I also broke it up so that at the end of each one, it felt like it was the end of the presentation.

So the first one was all about the mission and then it ended. And I wait to see what they'd say. And you know, a bunch of people say things like, “that's an amazing mission” or “I love what you're doing,” or “I could see how you could build like this” — In other words, they are going off and you're now having a good discussion.

So then I say, let me show you our product roadmap of what we're coming out with next. That was presentation two. So now you get a presentation two and you go through all the products and all this stuff. So we do that and as you get to the end, some people again get really excited — which is amazing!

And then you're like, let me show you the financials. And then you show the financials. Finally, they are like, “Whoa, this business is way bigger than we thought.” And you're like, yep. And if you get to that point, then you know you found the right investor.

But here is the funny thing. I once met with an investor in New York and then show them the first presentation. At the end, they're like, “that's great but it's a shame you don't have a good business.” And I was like, it is a shame. You're totally right. And I walked out the door.

So, we ended up raising the money and, blah, blah, blah, go through the thing, sell to Amazon, etc. After all of that, the same investor calls me up and is like, “What the &^%$? Why did you not tell me how good this, like this business was?”

And I said, because we were looking for mission backing investors and you basically disqualified yourself at the end of presentation one. There were two more presentations after that that you didn't get to see.

The Place of an Inventor in Business

Throughout our conversation, Jamie kept circling back to a simple but revealing truth: he’s a builder. Not just an entrepreneur, not just a CEO—but an inventor. The kind of person who wakes up thinking about what doesn’t yet exist and goes to sleep obsessing over how to make it real. Below, he parses those differences:

I look at myself as an inventor, which I think is a subset of entrepreneur. I think there's many subsets of entrepreneurs. think entrepreneur is a sort of a catchall phrase that we've come up with. When people say they want to be an entrepreneur, they often fail to realize that there's a number of different subsets of entrepreneurs. There's people that work within private equity and want to buy companies and make money. There's people that want to do public equity investment through stocks. There are people who want to do real estate. There are just all sorts of these verticals.

For me, finding problems and inventing solutions for them, that's what drives me. Invention is where I start. The business almost a second thought. I have a business because I have to, not because I want to. If I could invent without having a business, I'd actually be happy to do that.

I like this concept of an inventor in business — one who sees a problem and seeks a solution – and sometimes takes that idea to market.

Does this fit you at all?

I’ve always thought of myself as entrepreneurial, but I’ve never actually started a company. But what I really love is the act of invention—the process of tinkering, iterating, and figuring out how to make something work. So what if that, in itself, is a viable entrepreneurial model? What if the real game isn’t just starting companies but solving problems in a way that compels others to follow?

Age and Entrepreneurship

When Jamie Siminoff walked onto the Shark Tank stage in 2013, he wasn’t some fresh-faced college kid with a pitch deck. He was 36 years old with a five-year-old at home.

But is that unusual?

Not at all. In fact, if you look at the data, Jamie was even early compared to a certain kind of entrepreneurial sweet spot.

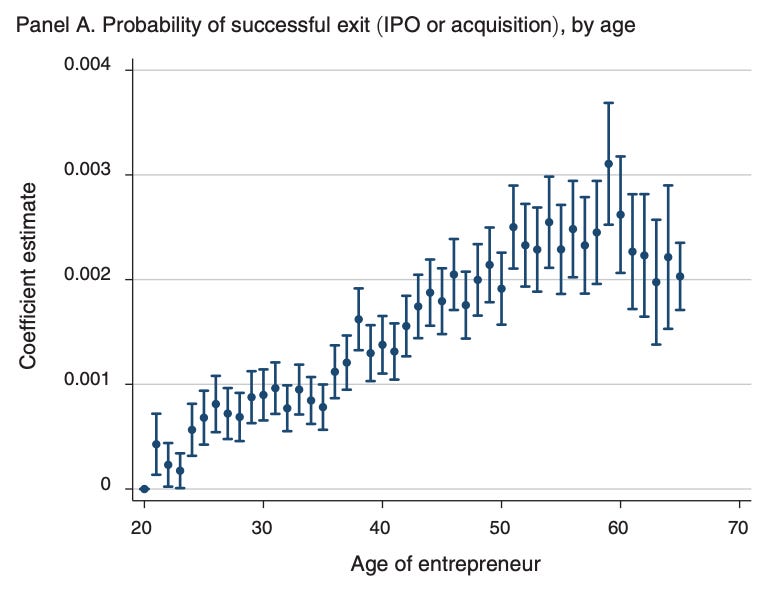

As I’ve shared in past episodes, the idea that the most successful founders are twenty-something tech prodigies is more myth than reality. A study in the American Economic Review by Pierre Azoulay and colleagues examined high-growth startups across industries. Their finding? The average age of a founder of the fastest-growing startups—yes, even the unicorns—was 45.

And it gets even more interesting: the data suggests that an entrepreneur’s likelihood of success increases with age—peaking in the early 60s.

So while Silicon Valley might celebrate the young entrepreneur, the numbers tell a different story. Experience matters. Pattern recognition matters. And, as Jamie’s story shows, sometimes the best entrepreneurs aren’t the ones just starting out—they’re the ones who’ve been at it long enough to know what works.

In other words, by all accounts, Jamie WAS a young investor/entrepreneur, and you and I might still have time!

From Inventor to Small-Town Community Development

One of the things I love about my job is that I get to move across the full spectrum of capital. One day, I’m talking to an entrepreneur worried about meeting payroll, and then next it is a philanthropist trying to figure out how to deploy capital in a way that makes a difference. Just last weekend, I spent the weekend with individuals in WashU’s bespoke philanthropy program — PhilanthropyForward — working with individuals seeking to refine their approach to philanthropic giving.

Jamie Siminoff is a perfect example of a person who has shifted roles.

His exit at Ring didn’t just mean financial freedom—it meant the freedom to build something new, and perhaps even invent for impact.

Research from Georgia Tech’s Paige Clayton and colleagues backs this up: entrepreneurs are far more likely than other wealthy individuals to jump into philanthropy after a big liquidity event.

Put another way: it’s hard to get the inventive impulse out of the inventor.

For Jamie, that meant a return to Shark Tank, an investment in a small Missouri-based company called Mooink, and, ultimately, a pull toward community development in the town where that company was based.

But as Jamie got into the latter part of this work, he didn’t want to shape a town by creating a destination — an amusement park or golf destination within driving distance of St. Louis. He wanted it to be more organic.

Below, Jamie reflects on parts of that work:

This is the toughest way to rebuild a town — not adding a destination piece to it and bringing in outsiders like me. Maybe this helps, but it also changes the community. It changes the structure. Specific to LaBelle, through investing in Lucinda, I got to spend time in LaBelle, Missouri. This town is about two and a half hours north of St. Louis — a small 700 person town.

Like many of these small towns, it had been hurt by several factors —the opiod crisis, industrialized farming, amongst others.

These towns are awesome but, sadly, in some ways, they are crumbling. When I got there, there were buildings, literally crumbling in the, in the center of this, of main district of the city.

And what that changes is perspective — the perspective of people. Money is a part of the challenge, but I would say its a 10 % component — 90 % of this is perspective. If people's perspective is that every day is going to be worse than the day they're in today, then they will throw a can on the street. They will not clean up in front of their yard. They will not mow their yard. Like if you think tomorrow's going to suck even worse than today, why would you do, why would you put a dollar into anything?

So Jamie did what any good inventor does—he started fixing things.

He got to fixing sidewalks. He added a coffee shop in the center of town — a place where people could meet, linger, and talk. He worked with local contractors to drive this work — creating new jobs along the way. In some ways, while Jamie was coming from an outside perspective, he wanted to sput a relatively bottom-up form of community building.

So, how do you know it’s working? Here again is Jamie:

I think success would be seeing the doctor's office and the daycare centers and the insurance companies coming back. It is seeing business owners who want to move there — businesses that probably wouldn't have otherwise existed.

I think a KPI that I would look for is signs of health signs in the downtown. For example, when you drive through the vacant lots — are they dirty or clean? As one example, there used to be just a lot of just junk on several of them. Now, the residents are cleaning them up, maintaining them. It seems to be driven by a greater sense of pride in the town — something intangible that you can feel.

I think probably the next thing I'd like to see is — and we're not there yet — is the value of homes increasing, and corresponding trust in investing in these assets. Again, I don't want it to be that the homes go from $150,000 to $500,000. That would be bad for the community because the people that own would just be selling and then be replaced by another person of the community.

Instead, I'd love to see some addition going onto a home… to see a new smaller home going up in a long vacant lot. In many ways, these are small signals of confidence returning — a different perspective.

There’s a lot more in the episode—more than I can do justice to here—but if any of this sparks your curiosity, I hope you’ll give it a listen.

In our next full episode, I get to share moments of a conversation with Daniel Lubitzky, the founder of KIND Bar. I hope you will join us!

Show Notes

If you are interested in learning more beyond the episode and newsletter, please find below a few resources we used in the generation of this episode: